Testing anti-patterns: Incidental coverage

So you’ve taken your project to 100% code coverage, you’ve configured your continuous integration system to fail the build if that coverage ever drops below 100%, and you’re ready to enjoy the fearless refactoring and the rock solid regression testing suite that your software engineering rigor has now earned you. But are you really covered? What does 100% code coverage mean in your project? Is it enough to know that your test suite encounters every line of code? Or don’t you want to be sure that it exercises every line? If you simply encounter the line without asserting that it produces the correct results, are you any better off? [1]

Failure to assert

Just achieving 100% code coverage is the easy part. Making it mean something: that’s where the real value kicks in. Consider the ease with which we can get to 100% line coverage on the following code (generated using Rails 2.1 scaffolding).

class ProductsController < ApplicationController

# GET /products

# GET /products.xml

def index

@products = Product.find(:all)

respond_to do |format|

format.html # index.html.erb

format.xml { render :xml => @products }

end

end

# ... remaining methods omitted

end

In order to ensure that the #index method is performing all its proper duties, we’ll define the following “test case.”

require File.dirname(__FILE__) + '/../test_helper'

class ProductsControllerTest < ActionController::TestCase

def test_should_get_index

get :index

end

# ... remaining tests omitted

end

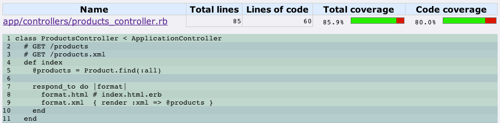

We’ll use rcov to assess the results.

And just like that, we have 100% code coverage for the #index method. [2] In this case though, that clearly means nothing more than the fact that we encountered 100% of the lines in the method. When code coverage is that easily achieved, it hardly seems cause for celebration. To get any real value from the test, we need to actually assert that we’re getting the expected results. Until we do so, we have nothing more than incidental coverage. [3]

The test code provided by the Rails scaffolding gets us closer to where we want to be.

require File.dirname(__FILE__) + '/../test_helper'

class ProductsControllerTest < ActionController::TestCase

def test_should_get_index

get :index

assert_response :success

assert_not_nil assigns(:products)

end

# ... remaining tests omitted

end

The tests pass, and our code coverage is still at 100%. At this point we’ve significantly increased the value of that particular test. No longer does the code have to crash spectacularly in order to yield a test error. Instead, exiting the method with anything other than a success response code will result in a test failure. Similarly, failure to set the @products instance variable will cause the test case to flunk. [4]

100% covered. 50% tested.

But while we’ve improved on the initial test case, at best we’re really only halfway to where we want to be. What would our test suite tell us if we were to alter line 9 as follows.

class ProductsController < ApplicationController

# GET /products

# GET /products.xml

def index

@products = Product.find(:all)

respond_to do |format|

format.html # index.html.erb

format.xml { raise :fatal_error }

end

end

# ... remaining methods omitted

end

$ ruby products_controller_test.rb

Loaded suite products_controller_test

Started

........

Finished in 0.17716 seconds.

8 tests, 15 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors

Unfortunately, our test suite still blindly gives a thumbs up, despite the fact that any attempt to access the XML-formatted output would yield an exception. While our test suite includes assertions for how the application should prepare an HTML-bound response, our coverage of the XML-specific logic in line 9 remains merely incidental.

If we want our automated test suite to ensure that the #index method remains capable of producing an XML-formatted response as our codebase changes over time, we’d need to add a test case to exercise that code.

class ProductsControllerTest < ActionController::TestCase

def test_should_get_index_formatted_for_html

get :index

assert_response :success

assert_not_nil assigns(:products)

end

def test_should_get_index_formatted_for_xml

@request.env['HTTP_ACCEPT'] = 'application/xml'

get :index

assert_response :success

assert_not_nil assigns(:products)

end

# ... remaining tests omitted

end

rcov doesn’t reward us with any extra credit for writing this test case, but achieving 100% coverage is not the primary goal of a good test suite. [5] The primary goal is to ensure that the code satisfies the requirements. If the application really is required to provide an XML-formatted list of products, then we should seriously consider defining a test for that functionality in our test suite. [6]

Size matters

In the examples above, we started off with a 5-line method that had 100% line coverage but lacked any assertions. That scenario provides some insight into other places where we might find a high percentage of incidental coverage. While long methods are a bad idea in general, the simple act of invoking a method may be enough to register it as having 100% coverage. If our test suite results in the execution of a 25-line method with no branches, all 25 lines are considered to be covered, regardless of whether we perform any assertions to verify the results of those 25 lines. Even if we refactor the code into smaller methods, if we don’t unit test those new methods, we’re still left with nothing more than incidental coverage.

Use it wisely

If your goal is to achieve 100% coverage, then incidental coverage is your friend, but your test suite will fall far short of its full potential. You’ll run the risk of acquiring a false sense of security, and the ability to safely and fearlessly refactor is out the window. Changes or enhancements to your application will occur without the safety net of a full regression suite.

If your goal is instead to develop a comprehensive test suite to A) validate your application’s functionality and B) ensure that you build just enough software, then test-driven development (TDD) is your friend (as are peer reviews and/or pair programming). And subsequently, you’ll enjoy the nice side effect of 100% code coverage, because you’ll only build the code necessary to satisfy your tests.

Notes

[1] Sure, you know that the line executes without causing the application to crash (at least for this set of inputs), but does a lack of crashing really constitute success? Not likely.

[2] While we have 100% line coverage for the #index method, we don’t have 100% coverage for the ProductsController class as a whole. As the full coverage report shows, the tests provided with the Rails scaffolding do not cover the exception cases in the #create and #update methods.

[3] Incidental coverage is just as valuable as that guy that puts in “face time” at the office. He’s physically present at least 8 hours every day. People see him there. He’s at the office. He must be doing something. Right?

[4] At this point we’ve gone from covering nothing to covering something. That’s good, but we should ask ourselves whether we’re performing the most appropriate assertions for this test case. For example, is it enough to assert that assigns(:products) is not nil, or should we be making a stronger assertion about its value? Do we want to ensure that we’re rendering the intended view templates? What about verifying the content of the HTML (or XML) that gets rendered? Tackling issues specific to testing Rails controllers would take away from the focus of this post, but the strength of assertions and the layers at which we test is surely fodder for future posts.

[5] However, with anything less than 100% coverage, fearless refactoring and full regression testing simply isn’t something your test suite can provide. In Software Testing Techniques (1996), Boris Beizer takes the hardline on anyone that would consider developing a codebase without at least 100% line coverage: “[Line coverage] is the weakest measure in the family [of structural coverage criteria]: testing less than this for new software is unconscionable …”

[6] You could argue that this new test case is too similar to the original test case, that it needs stronger assertions, or that the current functionality is too simple for this new test case to offer sufficient benefit, but it’s up to you to assess how important automated testing is of that code. If you opt to not test your application’s ability to provide an XML-formatted list of products, you must not allow your 100% line coverage to give you a false sense of security about your code. That code may be covered, but it’s not tested.

This post is part of the Testing Anti-patterns series: a series of essays taken from a conference talk titled, How To Fail With 100% Test Coverage.

–

Thanks to Stuart Halloway for reading drafts of this post.