A brief discussion of code coverage types

In any discussion of code coverage, it’s important to understand the type of coverage that’s being measured. In the same way that you wouldn’t plan a trip to the beach without knowing whether it’s going to be 30 degrees Celsius (perfect!) or 30 degrees Fahrenheit (stay home), we can’t have a truly meaningful discourse on code coverage without first identifying the analysis type.

Lining up

Many popular code coverage analysis tools currently report what’s known as line coverage (also commonly referred to as statement coverage). Line coverage analysis (as the name implies) identifies which lines were encountered as a result of your tests.

To better illustrate what we can expect from line coverage analysis, let’s first consider the following Ruby module and a possible test case for that module.

module Math

def max(a, b)

if a > b then a else b end

end

end

require "test/unit"

require "math"

class MathTest < Test::Unit::TestCase

include Math

def test_max

assert_equal 2, max(2, 1)

end

end

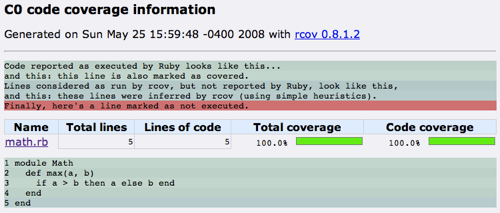

We can analyze this code using rcov, and we see the following results.

$ rcov math_test.rb

Loaded suite /opt/local/bin/rcov

Started

.

Finished in 0.00024 seconds.

1 tests, 1 assertions, 0 failures, 0 errors

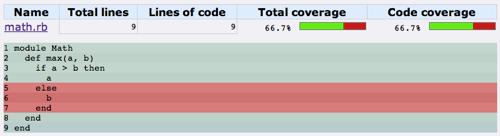

The coverage report assures us that our “test suite” has executed every line of code, and we’ve therefore achieved 100% line coverage (referred to as “CO” coverage by rcov). Before we celebrate, let’s consider what it would mean to simply reformat the code inside the #max method, without changing its actual behavior. By spreading the if-then-else statement across several lines, our line coverage suddenly becomes less admirable.

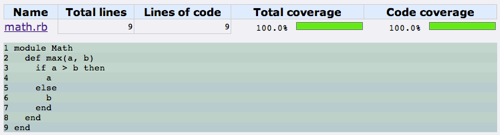

Of course, in reality, our test suite has been lacking all along. In both examples above, there are two possible branches of execution, but our test suite only exercises one of those branches. By ensuring that our test suite exercises both branches, we can easily make our way back up to 100% line coverage.

require "test/unit"

require "math"

class MathTest < Test::Unit::TestCase

include Math

def test_first_parameter_as_max

assert_equal 2, max(2, 1)

end

def test_second_parameter_as_max

assert_equal 2, max(1, 2)

end

end

As we saw above, while line coverage analysis certainly shows us when our test suite fails to execute all lines of our code, 100% line coverage doesn’t necessarily mean that we have a comprehensive test suite. Branch coverage analysis takes us a bit closer. [1]

Branching out

To see how branch coverage analysis would fare in the scenario above, we’ll pull in Cobertura to help us evaluate the equivalent Java code below. (Ruby doesn’t yet have a tool that provides branch coverage analysis, so we’ll use Java’s rich tool support for the remaining examples.)

public class Math {

public static int max(int a, int b) {

return a > b ? a : b;

}

}

import junit.framework.TestCase;

public class MathTest extends TestCase {

public void testMax() {

assertEquals(2, Math.max(2, 1));

}

}

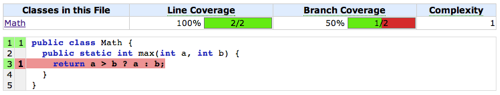

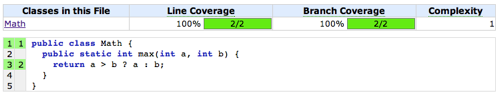

While Cobertura gives us proper credit for having 100% line coverage [2], its branch coverage analysis promptly identifies a weak spot in our test suite. As we saw above, when relying solely on line coverage analysis, we’d have to break our single-line if-else statement into multiple lines in order to detect this hole in our test suite. Branch coverage analysis, on the other hand, wastes no time in nudging us to exercise the other branch.

import junit.framework.TestCase;

public class MathTest extends TestCase {

public void testFirstParameterAsMax() {

assertEquals(2, Math.max(2, 1));

}

public void testSecondParameterAsMax() {

assertEquals(2, Math.max(1, 2));

}

}

The path not taken

Once we’ve made sure that every line is executed and each branch is tested in both possible directions, is there any remaining information that the field of coverage analysis can provide? To find out, let’s consider the following “enhancement” to our previous code samples. [3]

public class Math {

public static int max(int a, int b, int c, int d) {

int x = a > b ? a : b;

int y = c > d ? d : d;

return x > y ? x : y;

}

}

import junit.framework.TestCase;

public class MathTest extends TestCase {

public void testLastParameterAsMax() {

assertEquals(4, Math.max(1, 2, 3, 4));

}

public void testFirstParameterAsMax() {

assertEquals(4, Math.max(4, 3, 2, 1));

}

}

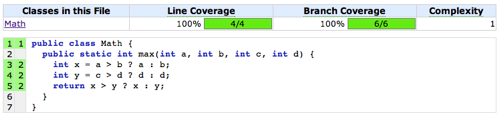

When we run our tests and analyze our coverage, we see that the two tests above indeed provide 100% line and branch coverage.

Despite the perfect score in those coverage types, our test suite is still lacking. If you look closely at line 4, you’ll likely see the bug that our tests failed to catch. There are a few important scenarios that our tests do not yet address. Those scenarios represent additional paths through the #max method.

While a single branch will have one of two possible outcomes, a specific flow through all the branches in a method defines a path through that method. For example, calling Math.max(1, 2, 3, 4) causes all three branches in the #max method to take the false route, thus making the path through the method false-false-false (FFF). So just how many possible paths does this method have? Given that we have 3 conditional statements, and each statement has 2 possible outcomes, we have 2^3 paths through the method:

FFFFFTFTFFTTTTTTTFTFTTFF

So far, our test suite covers 2 of the 8 possible paths (i.e., FFF and TTT), giving us 25% path coverage. [4] It’s only by testing the FTF path and/or the TTF path that we uncover the bug lurking on line 4.

public void testThirdParameterAsMax() {

assertEquals(4, Math.max(1, 2, 4, 3)); // tests the FTF path

}

Adding a test to cover that path not only increases our path coverage, but more importantly, it sends us into bug-fixing mode as well.

While analyzing path coverage can point you toward potential weak areas in your test suite, you’re unlikely to target 100% path coverage for your codebase. As the number of conditional statements grows and as you introduce common looping constructs, you can quickly find yourself facing a combinatorially explosive number of paths. [5]

Use it wisely

While this is by no means an exhaustive list of coverage types, it’s representative of the types of coverage analysis you’ll most often find used in practice. And from the examples above, it’s easy to see just how very different these measurements can be. When measuring or discussing coverage, be sure to ask what type of analysis is being performed to ensure meaningful interpretation of the results.

Code coverage analysis is an essential tool in evaluating the quality of your test suite. But as with any metric, it shouldn’t be used in isolation. In How to Misuse Code Coverage, Brian Marick reminds us that “[coverage tools] are only helpful if they’re used to enhance thought, not replace it.” [6] And in a series of upcoming posts, I’ll explore that idea further through discussion of several testing anti-patterns observed in real-world projects.

Notes

[1] Despite this shortcoming in line coverage analysis, I don’t recommend expanding code onto multiple lines just to get a more thorough coverage report. Instead, understand the capabilities and limitations of your coverage analysis and keep that information in mind during peer code reviews and quality assurance testing. In What is Wrong with Statement Coverage, Steve Cornett offers additional code samples illustrating scenarios where 100% line coverage could give you a false sense of security if used in isolation.

[2] Actually, in order for Cobertura to report 100% line coverage, it requires that we instantiate a Math object somewhere in our test suite. Even though the Math class is only intended to provide a single static method at this point, Cobertura will report line 1 as uncovered unless we invoke new Math(); somewhere in our test suite. I omitted that statement from the test code above for the sake of brevity, but the report shown above is the result of running against code that included a call to new Math(); in order to show 100% line coverage. (Future posts will discuss some of the hoops you occasionally have to jump through to reach 100% coverage and the tradeoffs associated with confronting those issues.)

[3] This code is admittedly ripe for refactoring and suffers from multiple code smells, but it illustrates the point nonetheless.

[4] A formal explanation of paths would quickly derail this “brief discussion of code coverage types” into an exploration of cyclomatic complexity, the exponential growth effect of decision points on paths, linear independence, etc. For additional information on this topic, I recommend reading Steve Cornett’s explanation of path coverage and the various resources he cites.

[5] A subset of path coverage, known as basis path coverage, attempts to reduce the number of test cases needed to sufficiently exercise your code. While achieving full basis path coverage increases the likelihood of exposing branch-based bugs and is more feasible than reaching 100% path coverage, it’s possible to choose a set of basis paths that allows bugs (including the one in the example above) to remain hidden.

[6] As the man behind testing.com for more than a decade and the creator of four coverage tools, Brian knows a thing or two about this topic.

If you enjoyed this post, you may also enjoy the Testing Anti-patterns series: a series of essays taken from a conference talk titled, How To Fail With 100% Test Coverage.

–

Thanks to Stuart Halloway and Rob Sanheim for reading drafts of this post.